In Pellot’s Old Quatrian Review (1840), we find references to and descriptions of the Grand Theatre of the Hypergeic Temple. The House of Song ruled during this age, and the spectacles and mystery plays of the period reflect the complexities of the Quatrian Post-Shapist architecture of the time, which itself reflected the cosmology of the era.

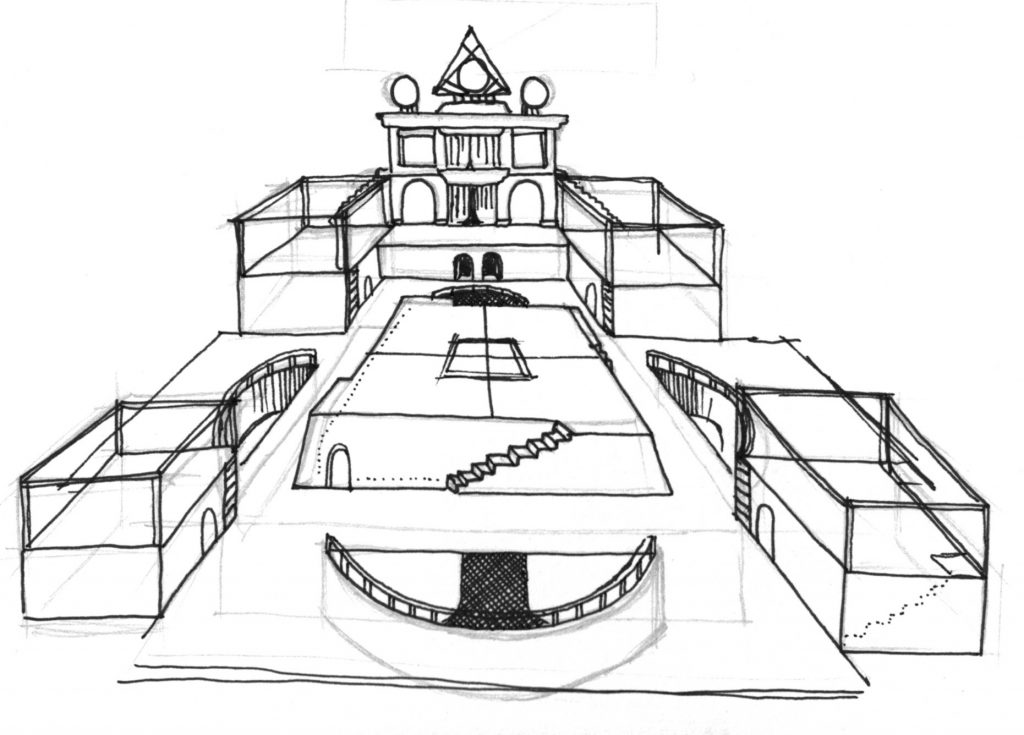

Figure 1 below is an artist’s reproduction based on the description found in Pellot’s Review, and which is itself variously attributed to traditional sources. However, many leading Pantarctican authorities of today suspect certain details contained in the text might have been at least partly inspired by Pellot’s own analeptic journeying.

What follows is a excerpt, lightly edited (for clarity), from the Pellot, describing what he calls the Quatrian “Theatrum” during the Age of Song.

The Theatrum was the axis mundi of the Hypergeic Temple during the Age of the House of Song. It was literally built over an entrance leading down into the Hypogeum, and the rest of the Hypergeic Temple was built around this most important landmark in Quatrian culture. For in ancient Quatria, all things were understood to come from, and eventually to return to, the depths of the Hypogean underworld.

The central platea, or stage, was where the majority of the action took place within a given play or cycle. It was elevated from the ground above the heads of men, and doors issued forth on all four sides, such that the priestly performers could enter, cross, and exit by other stage locations via an elaborate network of tunnels. Stairs, likewise, flanked the four corners, one for each House into which the stage was divided. And in the center of the platea were four trap doors, one for each House, which connected to the network of tunnels below, and ultimately to the Hypogeum itself.

Sunken down into the ground, one on each face, were pits for orchestras, of which there were a total of four. As the action moved around the stage and adjoining mansions, each corresponding orchestra would make its musical contribution. The orchestra pits, likewise, had communicating passageways into the sub-tunnel system, below that of which was used by the priestly actors, such that the sound of their performances was more easily able to resonate down into the Hypogeic realm, to appease the hosts of listeners there.

At each corner of the platea was a raised mansion, one for each House, which represented specific locations, and which could be fitted out to have a second floor (with additional special musicians sometimes being housed on the first). During the course of a play or cycle, the actors and action would move from mansion to mansion depending on the needs of the narrative, with the music of the four orchestras following in support.

The mansions assigned to the House of Sorrow and the House of Silence were linked by a two-level construction known simply as the Palace, such that an actor could cross between the two, or mount a stair to the second level.

With the centrality of these theatro-musical performances to Quatrian life and culture, it would be a gross anachronism to compare the Theatrum to today’s vulgar “entertainments.” Their import was most grave, as they were considered to be not mere diversions, but direct communication with the mythic gods, heroes, and tales upon which their entire lives were patterned, and which they believed their own existence was dependent. Attendees at these cyclical festivals were not audience members, but engaged in a vital ‘participation mystique’ with the imaginal realm which peopled and overlaid their landscape. By actualizing their myths together societally, they saw themselves as perpetuating an unbroken line of transmission between the past and future, such that all were one. And they concommitantly believed that their glorious culture would continue so long as the performance of their rituals did. History would prove them, of course, more or less correct in that regard.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.